Feliciano Ramirez Rimachi bears witness with his hands — gnarled, beaten hands, each missing a finger, gripping a worn Bible.

They tell of the day in 1988 that he pulled up a Shining Path flag — red, the signature color of the Maoist group — from the earth of Carhuahurán, his highland Andean village in Huanta province. The terrorists, anticipating this, had planted explosives around it.

“I heard a sound like a match striking,” he says. “I tried to throw the bomb away, but it exploded.”

The act made Feliciano a war hero. Then he became a mayor. But his abiding purpose is maintaining his community’s memory.

He tells their story — a story of resilience. He has told it over and over, to visitors, journalists, and researchers. It’s important to tell it right.

“We were living around death every day, afraid of terrorists and soldiers,” Feliciano says. To ward off the mountain cold he shoves his hands deep into the pockets of a jacket that was once trimmed with leather, now worn off.

He starts when the Shining Path first came in 1978. “They were a group of students from the University of Huamanga,” he says. “They didn’t come to kill. They came to make people know the Shining Path doctrines.”

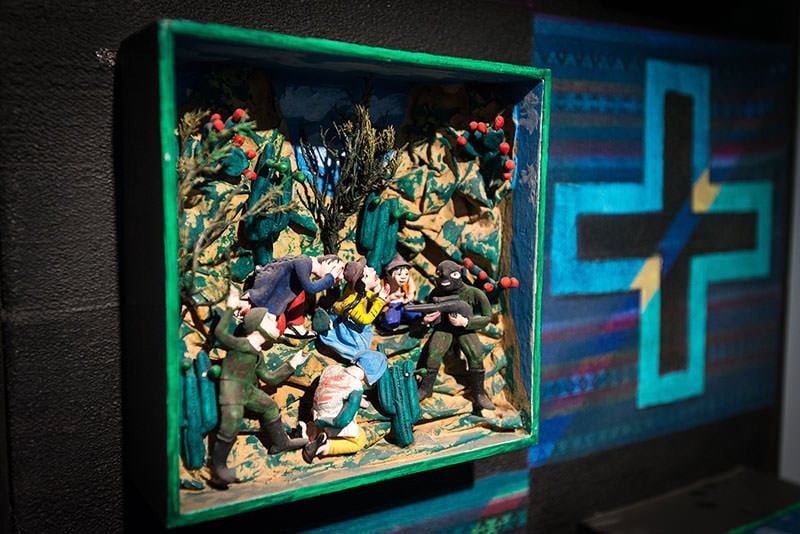

The brutal tactics of masked soldiers are shown in this museum retablo, a traditional Andean art form.

The students annoyed people at a festival, and authorities whipped them. Two years later, on Christmas Day, the rebels — now enforcing their ideology with guns — killed seven people. “The seven people were the ones who had whipped the students,” he said.

There were more killings that year, and by 1980, villagers were terrified. “We slept in the mountains. There was nobody in Carhuahurán during the night,” Feliciano says. “We hid in caves.” Villagers formed rondas campesinas, patrols to watch out for terrorists.

Similar events played out all over rural Ayacucho, one of Peru’s poorest regions. Shining Path leaders, who came from this area, claimed to represent the disenfranchised indigenous people. But theirs was a zero-sum game: Join them or die.

The military moved in, but instead of protecting villagers, they brought more bloodshed. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, armed forces committed widespread human rights violations under the banner of crushing terrorism.

Faces of the courageous members of ANFASEF, a women-led association, remind visitors to the Museum of Memory to never forget what happened to their loved ones.

In Carhuahurán, where they set up a post, “Soldiers became like the boss,” says Feliciano. “We couldn’t work the land. We had to support the military base with wood and food.

“We had to help look for terrorists, and the soldiers made us go ahead of them,” he says. “We were closer to death than anybody.”

Feliciano, an evangelical Christian, took comfort in knowing God was with him. The words of Genesis 28:15 — “I am with you and will watch over you wherever you go” — became his favorite Scripture.

And yet Feliciano, like many in Carhuahurán, didn’t go. They stayed, surviving both the terrorists’ attacks and the military occupation.

“We were closer to death than anybody.”

– Feliciano Ramirez Rimachi, former mayor

His story is about their strength. His hands testify to the cost.

About 78 miles away — and many hours of driving on mountain roads — in the regional capital, Ayacucho city, another group focuses on remembering.

The National Association of the Families of the Kidnapped, Detained, and Missing of Peru (ANFASEF) started as a group of women who just wouldn’t stay quiet. Their husbands and loved ones had been arrested, murdered, or — that terrible word — disappeared. They marched and demanded answers, despite the danger in doing so in the 1980s.

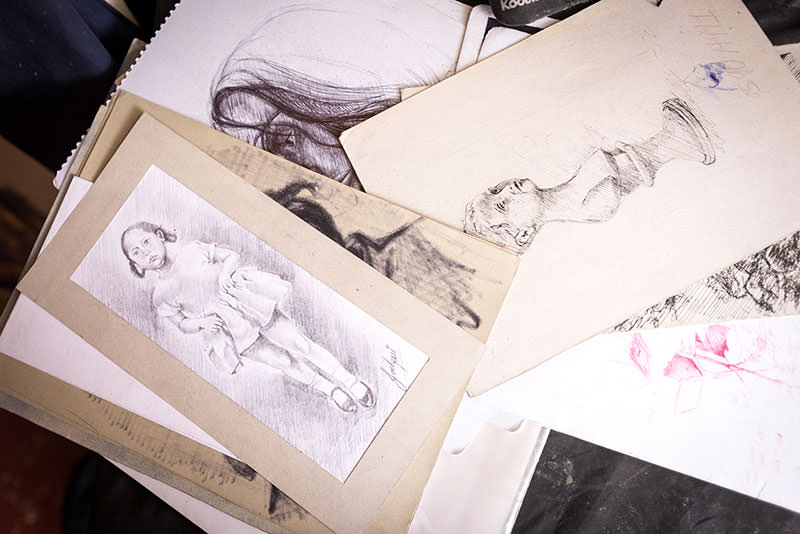

The group created a Museum of Memory that uses photographs, traditional art, scene recreations, interactive exhibits, and artifacts to convey atrocities committed by all perpetrators.

The result is a visual history of the Shining Path era, elaborated by the thorough narration of an ANFASEF member. You hear about the slaughter of more than 100 people in Putis, gunned down after soldiers ordered them to dig a trench, supposedly for fish. You learn about the execution of six men whom soldiers dragged out of a church service in Callqui and shot while the rest of the congregation were forced to keep singing. You see a recreated cell in the Huanta soccer stadium, used by the military to torture suspected terrorists.

Empty clothes, donated by relatives, represent missing men, women, and children.

A woman’s written testimony explains the significance of a little metal pot, given to her by a soldier after he was done feeding his dog with it. “If this little pot had life, it would tell everything,” she writes.

An exhibit called “Two Faces of Death” features a twin display of traditional dioramas detailing the horrors. On one side, set in a red design, those committed by terrorists: beheading, stoning, killing village authorities. On the other side, in green, are crimes by soldiers: tossing people from helicopters, burning bodies in ovens, killing innocent family members.

Death had two faces during the Shining Path era: terrorists (red) and the military (green) — with Quechua villagers caught in between.

The ANFASEF women speak for the missing and the victims who, all these years later, are exhumed from shallow graves, their remains returned to family members.

Of the nearly 70,000 people killed from 1980 to 2000, three-fourths were indigenous or Quechua-speaking people.

“Para que no se repita,” the museum tour concludes. So this never happens again. That, after all, is the point of remembering.

The survivors tell their stories. It’s important to tell them right.

![Denisse is pictured in 2014 at the Huanta municipal building in 2014 where she works as a mayoral adviser — the youngest person elected to the position. She credits her success to her experience with the Children’s Parliament as well as her sponsor’s encouragement. “My sponsor wrote [letters] in a very lovely way, like I was her daughter,” Denisse recalls.](http://wvusstatic.com/2019/peru/assets/content/then-and-now/denisse/02-800.jpg)

![Emiliano and Gladys have mostly retired from leadership in order to focus on their family and financial future — Gladys has a thriving business at the Huanta Sunday market. Three of the couple’s children are college-educated. “We learned in [World Vision] trainings that we should have a vision for children,” says Emiliano. “ ‘Do you want your children to be just like you?’ No — to be better.”](http://wvusstatic.com/2019/peru/assets/content/then-and-now/gladys-and-emiliano/02-1200.jpg)